Rani Bala and her eight-month-old son Bikash are nowhere to be seen when we approach their bed on the women and children’s ward. Neither is her songi, who might have been able to explain their absence. Most mothers have a songi, a female relative, with them most of the time when they are in hospital. She cares for their basic needs, helps with their child, does their washing and provides their food. In fact, Rani does not have a songi.

A nurse goes in search of Rani and she finally enters through the curtain which divides the women’s ward from the men’s. She is tall and slim and holds herself erect. She sits on the side of her bed and places her son down on the bed for the doctors to look at. He had been admitted with a chest infection and has been treated with antibiotics. His infection is now almost better, but other things about him and his mother cause us concern. Bikash is thin, malnourished and listless. He allows examination without any resistance and Rani sits impassively by, with little care for her son – so different from most of the mothers, who cradle their children in their arms as they sit cross-legged on their beds. She answers our questions in monosyllables with an emotionless face, looking at us with big, round, sad eyes. Something is very wrong here. What is it?

What’s going on? We turn to Bikash’s notes and find out that he has been fed on formula milk from birth. This is very unusual here where breast-feeding is almost universally the norm – for financial reasons if nothing else. We find out, with some difficulty due to Rani’s unwillingness to talk, that Bikash is still fed formula milk and has some family diet – rice, dahl and so on – as well. We are dubious as to how much he has, as he weighs only just over five kilograms, way below the average for his age. We then enquire about what Rani and her child have been eating while in hospital. Feeding patients is not a hospital responsibility. Food is brought in by the patient’s family, or bought by the songi at the gate (there are several roadside cafes just outside the hospital entrance) or from the food supplied by the kitchen here. Little food had been brought in for Rani and her son during their stay, and so it was not surprising that Bikash’s weight was falling still further since admission. Had he had any food in the three days since admission? A food slip can be provided to folk such as Rani so that she can buy hospital food cheaply. We provide her with such a slip, encourage her to use it and walk away. The look in Rani’s eyes made me uneasy. What is her story?

The next day we come to Rani and Bikash’s bed and once more find it empty and we have to find them. Bikash has not gained any weight, and both he and his mother look listless. It transpires that Rani refused the hospital food. I take a nurse aside and try to find out Rani’s story – and then I understand. Rani looks to be in her mid-twenties but is, in fact, only fourteen-and-a-half years old. She was married at thirteen years and bore her son, Bikash, ten months later. Her husband has deserted her, and she has gone back to living in her father’s household; probably not a happy situation. No wonder that she is depressed.

No kind of ending We return to thinking about what can be done for Rani and her child. We find that they do not live far away but it is not in an area where the LAMB Project has clinics. Then, the doctor has an idea – perhaps Rani could bring Bikash to the Rehabilitation Centre each week for weighing and could receive help, advice and support while there. It is all we can do except encourage her to eat nourishing food and give some to Bikash. He is nearly ready for discharge as far as his chest infection is concerned, and we can’t keep him in for ever. Once again we walk away. We can do so little to help in such a situation. I feel tears welling up in my eyes.

At lunchtime I make a point of going through the ward and am encouraged to see Rani feeding Bikash with some of her food, although whether it was any more than rice I could not see. I smiled at Rani and got a hint of a smile back. How I longed to be able to tell her of the One who most certainly loved her and her son more than ever I could.

The next day, I visit the ward and go to Rani’s bed. It is empty, with no sign of Rani’s or Bikash’s belongings. I am filled with apprehension. Has she gone? I find a nurse, who tells me that Rani has discharged herself. Did she do this under compulsion, I wonder, or had she done it willingly? Was it really what she wanted? Had we been too intrusive? A sadness fills my heart. What will become of Rani and her son now? But then I realise that, though they are out of reach of LAMB for the moment, they are not out of reach of our loving heavenly Father, and I resolve to pray and trust Rani and Bikash into his hands.

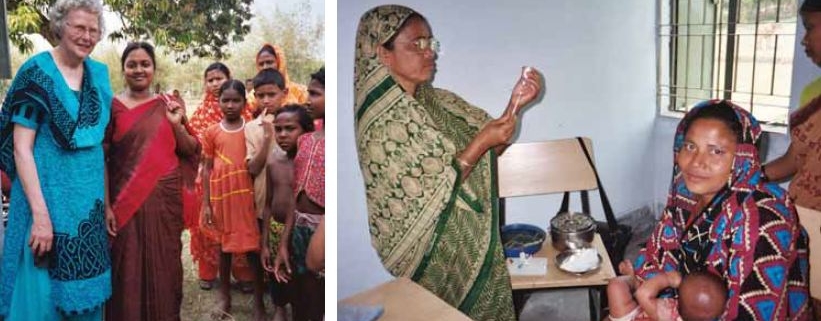

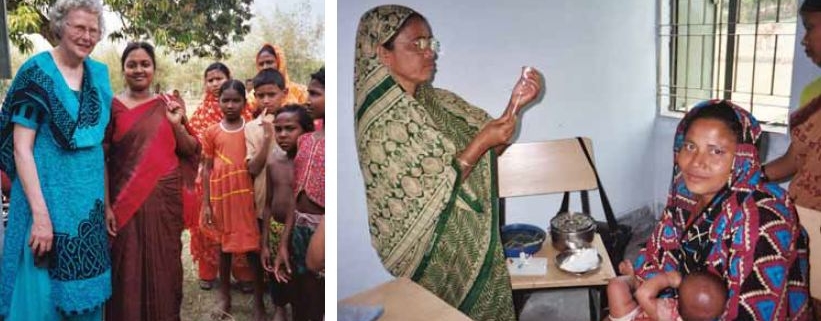

Cecilia, in her early 60s, went out from her church in the UK, through Interserve’s On Track short-term programme, to the LAMB Project in rural north-west Bangladesh for four months last year to help in the setting up of a children’s nursing course in the 75-bed hospital there.